I’m working on an epic book that’s coming out in May this year: Bosnian War Posters, by Daoud Sarhandi. It’s an incredible collection of propaganda and art that he and Alina Wolfe Murray, my ex-wife, collected just after the war in Bosnia Herzegovina. It’s taken a long time to come to life but that’s another story.

The posters are arranged chronologically, with long captions, and it tells the story of Bosnia’s war. Young people in Bosnia Herzegovina are particularly interested because they don’t learn about the war in school – it’s too recent, too raw, too politicised – and they want to learn about it so they can avoid the mistakes of their parents. Young Bosnians also want to see how people communicated before the internet.

Many of the older Bosnians I’ve met, those who have experienced the war, don’t seem very interested in it; on the one hand they want to forget, while on the other hand they can’t stop thinking about it (or so I’m told).

Could we do books like this in other war-torn countries?

The reason I’m putting this article together is that I got a very inspiring audio messages from the author, on WhatsApp. It was in response to a discussion about possible future projects we could do in other parts of the world. “Surely”, I asked Daoud Sarhandi, “we could repeat what we did in Bosnia-Herzegovina? Surely there would be great material in other war zones, as good as what we had found in Bosnia?”

Daoud’s audio message (which I’ve transcribed below) gave me the insight I’d been looking for; it answers the question I’ve been asking myself: what makes our book, Bosnian War Posters, unique?

This is what Daoud said:

“The thing about Yugoslavia is that all the stars were aligned. We were in the right place at the right time, in a country which had a conscious design memory – or history – connected with Europe and Russia. One of our contributors, Bojan Hadžihalilović, says the war happened just before the internet and social media came into its own. I think the great poster campaigns the world witnessed in the past are over. Bosnia may have been the last war that used posters to such effect.

“Artists like Began Turbić, Asim Đelilović, and others are valuable as their posters and concepts are original, unique, and self-generated. I was recently thinking about doing a similar book about the Spanish Civil War as some of the work is beautifully drawn and designed. However, Spanish Civil War posters were produced by propaganda agencies on both sides rather than individual artists. They were just churning out very formulaic stuff and you actually learn very little from this material about the war as a whole, or what the people were really feeling. That’s not true about the posters we found in Bosnia Herzegovina. I think Began Turbić’s work, for example, is stunning compared to anything that came out of Barcelona or Madrid.

“Also, the only surviving Spanish Civil War posters are from the conquered cities. There’s almost nothing from small places and nothing independent left. This is not true of the material we found in Bosnia Herzegovina, as we were able to visit the most remote locations just after the war as well as scores of individual artists.

“What we found is absolutely unique. Not only in terms of Bosnia-Herzegovina, but in terms of world heritage. I can’t think of any war in history that generated such a rich heritage of original poster art, and the interesting thing is that it was genuinely independent in that most of the work we collected was produced by individual artists, working alone, and the government and army seemed to ignore them. It was a moment in time that’s not going to come back. It was something that doesn’t happen everywhere and probably will never happen again.

“In 2004 I went to Palestine to investigate doing a poster book about the Israeli/Palestine war. I travelled with an expert in the field, Dana Bartlett, an American design professor teaching in Prague. She’d already done an art book on some of those posters called Both Sides of Peace. At my suggestion, we went to do another book, a bigger one, and I spent two months in Palestine, mostly in Ramallah, talking to artists and designers, as I had done in the former Yugoslavia (in 1997/98). I thought I could repeat the process in Palestine.

“But all I found was visual dross. A lot of great people, for sure, and some great artists – but no inspiring design. What I found was loads of photoshopped posters with the words Islamic Martyr in Arabic, and a young guy holding up an AK47. After you’ve seen a hundred of these posters – which are more of less the same – you realise there’s no story of design here. I understand it culturally, and I respect it, and in its own way it is interesting, but it isn’t artistically inspiring or even very educational.

“But my Palestinian trip wasn’t wasted as I ended up making a great documentary film, The Colour of Olives.

“Sophisticated design doesn’t really happen in most countries. You could go to loads of conflict zones – Iraq, Syria, Rwanda, Yemen, wherever – and I’m sure you wouldn’t find much – you wouldn’t find a body of design work expressing lots of different aspects of the experience. You might find one or two artists doing something interesting, or quirky, but you wouldn’t find enough for a book. And then you’d have to know a lot about the war. To do what we did with the captions, you’d have to know all the ins-and-outs of that conflict.

“Islamic countries are particularly problematic in this design regard, which is why Bosnia Herzegovina was such a unique situation because there’s an Islamic element in this very special European country. But Islam generally is not very encouraging about modern graphic design. It’s just a fact. If you look at the history of Islamic art, it’s mainly decorative. When I met graphic designers and illustrators in Palestine they complained to me about this, that Islam doesn’t doesn’t like art to be confrontational. Art in Islamic countries celebrates the divine; flowers, symmetry, and non-human representation. You get lots of floral motifs, and calligraphy, and very little that is confrontational in the way that western audiences understand it. It’s a different thing altogether.

“Could we do a poster book in Lebanon? I doubt it. Syria? I don’t think so. What’s more I’ve got no motivation to do a big investigation, going round knocking on doors in another country. I don’t have the energy for that, plus I have a young family that I can’t just leave.

“I’m very, very proud of Bosnian War Posters. As a book it’s beautiful and we managed to save so much of the Bosnian’s wartime experience that would undoubtedly have been lost. As far as I know, we were the only people going around collecting all this material in a systematic way. I think the Bosnians didn’t quite appreciate its value, plus they were exhausted after the conflict. They’d had enough of the whole bloody mess. Sometimes outsiders see things that locals don’t in this regard – the distance helps. I knew from the go get that it was all very special and I’m glad we helped to preserve this bit of their cultural heritage.”

What’s unique about this book of posters?

There is a second part to answering this question: putting it into context. This was done rather brilliantly by Carol A. Wells, who runs the Center for the Study of Political Graphics in Los Angeles. She wrote a foreword which puts the book into historical and artistic perspective:

“It is not surprising that so many artists made posters during the Bosnian War as they are one of the most accessible, easily disseminated, and popular art forms to express conflict and resistance. What may surprise those who are seeing these posters for the first time is their variety, abundance, and often extraordinary design…

“Although few of these Bosnian posters are well known, many of them may look familiar because they incorporate images from advertising, fine art, film posters, album covers, and popular culture…

“The Bosnian posters in this book incorporate Western art from prehistoric to Renaissance, from Pop to Punk. The referenced art includes work by Massacio, Durer, Leonardo, Picasso, and Warhol. Posters that were originally made for World Wars I and II, and the Spanish Civil War, were ‘redesigned’ for the Bosnian War. The familiarity of these shared cultural references draws us in.”

#

Artists in Bosnia Herzegovina were able to draw on this rich history of ancient and modern art as many of them had been through a classical education at Sarajevo’s renowned School of Art, where great art is studied over many years. I was at this art school recently and can confirm that it’s still going strong — and the students I met are very keen to see our new book of wartime posters.

My own interpretation of the Bosnian War posters is that it was the only way that artists in Bosnia-Herzegovina could protest about what was happening. As electricity was heavily restricted, the only mass media they had occasional access to was the radio. These shortages made the poster all the more powerful as a means of communication. The same didn’t apply to the other warring parties, Croatia and Serbia, which had fully functional mass-media and national propaganda systems. Although we collected some posters from these countries, very few wartime posters were produced as they didn’t really need them. But we got a few from the start of the war in Croatia as well as some interesting magazine covers from Belgrade.

What I didn’t appreciate until very recently was the level of freedom Bosnian artists had to express themselves – which is ironic considering that the Bosnian people were effectively hemmed in, geographically, by their enemies. They were imprisoned by external forces but their spirits were free.

A Sneak Peak

Finally, I’d like to share with you a couple of images from the book, and I’ll quote from Carol Wells’ foreword which puts them into context:

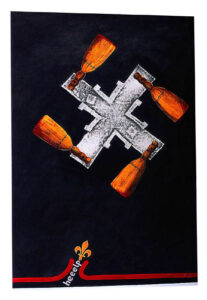

“A poster titled ‘HEEELP’ by Began Turbić used photomontage to transform an Orthodox Christian-style cross into a swastika by attaching traditional peasant-made brushes to the ends of the cross. Sixty years earlier, the German artist John Heartfield used this technique to create a swastika out of four bloody axes. Heartfield’s 1934 work was ironically titled ‘Blood and Iron,’ which was the motto of the Third Reich.

“Heartfield was one of the originators of photomontage, and made many anti-fascist magazine covers and posters using this technique. Turbić’s use of photomontage to create a swastika thus connects the past with the present. The average viewer may not have known this reference, but it would have been recognized by other political poster makers, as Heartfield is often considered one of the earliest designers of mass-produced protest posters.

- John Heartfield’s 1934 poster “Blood and Iron”

- Began Turbic’s Bosnian wartime interpretation.

Find out more

We’ll be launching a crowdfunding appeal soon, to offer discounted copies of the book to Bosnians everywhere as well as anyone who supports this great country. If you’d like to get more information about this please send me (Rupert) an email: wolfemurray@gmail.com

The headline photo of this article was produced by Trio studios during the war. It’s a re-interpretation of the Coca-Cola symbol and it’s printed on the back of an old army map, as paper was in such short supply.

If you’d like to see more of the Bosnian War Posters just follow this hashtag on Instagram: #bosnianwarposters

As always, I’d be most grateful if you could leave a comment under here. All feedback is useful, every voice is valid and every perspective is true to itself. I’m particularly keen to hear from young Bosnians as I’ve been so impressed by those I’ve met so far. I intend to give more talks in Bosnian schools when I go back to Bosnia Herzegovina later this month.

Finally, if you’d like to know why I got involved in this project, see this article: Why I moved to Bosnia

- Introduction to 12 Jobs in 12 Months - April 23, 2024

- Why am I writing a Book About 12 Jobs in 12 Months? - April 4, 2024

- A Guide to Ukraine’s Future - February 19, 2024