If a great artist met a convicted murderer I wouldn’t expect much to come of it. In most cases, I assume, nothing more than an ordinary conversation would happen for the simple reason that the prisoner wouldn’t be open to the artist. The prisoner might view the artist with suspicion.

The prisoner might be friendly, he might be grateful for the attention being paid to him, but he wouldn’t risk lowering the barriers that are so essential for his survival on the “inside”.

But when Jimmy Boyle – once known by the Scottish tabloids as “Scotland’s most dangerous criminal” – met Joseph Beuys who, according to The Tate Gallery is “widely regarded as one of the most influential artists of the second half of the 20th century,” the results were remarkable.

The meeting was part of Boyle’s transformation into a celebrated artist, but it’s a complicated story to tell as there are, as far as I’m aware, no written records of the meeting. Also, there’s virtually no written records of the most successful experiment in prison reform I’ve ever heard about – the Barlinne Special Unit, where Scotland’s “most dangerous” criminals were on equal terms with the prison officers and their “therapeutic community” was a runaway success. Luckily, the artworks, press clippings and writings that emerged from the Special Unit are held in various private collections around the country.

Tragically, the reactionary officials in charge of Scotland at the time were embarrassed by the success of the Special Unit and they did nothing to stand up to the daily assaults by the tabloids, who screamed of sex and drugs and luxury for the most violent prisoners in the land. In 1994, 20 years after the unit had opened, it was quietly closed down. Not even the most basic written evaluation was done.

I just checked the website of Scottish Prison Service and the only reference I could find for the Special Unit were the following words in their list of historical events at Barlinne Prison: “1972 Special Unit in Female block (until 1994).” Is that really it? Looking at their website I realise that the only thing that has changed over the last half century is the language they use to present themselves; now the prison service talks about “individuals in our care” and their main slogan is “Unlocking potential. Transforming lives.” As my kids would say with a roll of their eyes, “Really?”

Scotland’s puritan leaders may have thought they succeeded in burying this success story, but it got out. The success of the Special Unit’s therapeutic community model reached less closed-minded governments in Scandinavia and the Netherlands where, according to my sources, similar units were set up. Also, the prison in Hull set up a large art class that was inspired by the Special Unit. Bill Beech, one of the artists who has kept this flame alive, organised the current exhibition of Special Unit artworks in Hull. Apparently, there is also a prisoner at Hull who dresses and acts like Joseph Beuys (presumably he also does experimental art works).

Back to the Boyle and Beuys story…

Before getting to the meeting between Boyle and Beuys I need to describe more background (as I said, it’s a complicated story, but it’s a great one so stay with me).

Both of these men have the most incredible backstories; Jimmy Boyle’s can be read in his two autobiographies – A Sense of Freedom and The Pain of Confinement. What I find most remarkable about these books is his ability to be so open and descriptive about the poverty he grew up in; I had assumed that they were ghost-written as they’re written with such confidence but I asked his former wife, Sara Trevelyan, and she said “No. Jimmy definitely wrote them on his own”.

Joseph Beuys’ backstory reminds me of a Greek myth: a man falls from the sky in a ball of flame; he survives the fall and is buried in snow; later he’s discovered by nomads who wrap him in grease and felt, carry him off, nurse him back to health; he goes on to great things.

The Wikipedia version of the story makes it clear that this story is probably just fantasy, but the known facts are equally incredible: Beuys joined the Luftwaffe (Hitler’s air force); he was stationed in Crimea during the German occupation of the USSR; he was a rear gunner on one of the most terrifying weapons of the Second World War – the Stuka dive bomber. It’s also interesting that the supposedly heartless German’s sent out a search party to find him and the pilot who, according to Beuys’ version, was “atomised” when their plane crashed.

Beuys’s later wrote: “Had it not been for the Tartars I would not be alive today. They were the nomads of the Crimea, in what was then no man’s land between the Russian and German fronts, and favoured neither side…Their nomadic ways attracted me of course, although by that time their movements had been restricted. Yet, it was they who discovered me in the snow after the crash, when the German search parties had given up….I remember voices saying ‘Voda’ (Water), then the felt of their tents, and the dense pungent smell of cheese, fat and milk. They covered my body in fat to help it regenerate warmth, and wrapped it in felt as an insulator to keep warmth in.”

In terms of art, the above story is referred to as Beuys’ inspiration for using a lot of felt and other natural materials, like stone, in his work. The clothes he wore were also influenced by this experience – his trademark clothing was a felt suit, a stick and a felt hat.

In terms of the Jimmy Boyle connection, I see this story as the experience that connected them. What I mean is that Beuys was a form of prisoner in the Second World War, an unwitting participant in a brutal system that had much in common with the guiding philosophy of modern prisons: to remove peoples’ liberty and enforce a rigid daily routine that instils fear and destroys individuality.

I’m not saying that the Scottish Prison Service can be compared to the Nazis in terms of human rights abuses, but you can compare the underlying philosophy which is that denying people liberty and applying a strict military routine is morally justifiable.

My assumption is that these shared experiences – of deprivation, horror, death, redemption – brought the two men together in a deeply profound way that would not have been possible between people who didn’t share those type of traumatic experiences.

Enter the coyote

Joseph Beuys went on to become one of the most influential artists of his age. Beuys’ saw himself as a teacher, or shaman, who could guide society in a new direction.

He was thrown out of the Düsseldorf Art School, where he taught sculpture, for getting rid of the entry requirements and advocating a policy of letting anyone interested into his classes – a direct challenge to the art world’s ethos that art is only for an intellectual elite. His most relevant work in this regard was a performance art “Action” called How to explain pictures to a dead hare, when he explained art for three hours to a dead hare. The idea was to show “the difficulty of explaining things” to people who aren’t educated in the language and history of art – in other words the general public. This was part of his overall belief that “everyone is an artist”.

In the early seventies Beuys was invited to put on an exhibition in the USA. He refused because he was an opponent of the Vietnam War and would not set foot in the country that was perpetuating such horrors on a less technologically advanced people. But the Renne Block Gallery, in New York City, persisted and they came to a compromise out of which a quite remarkable exhibition resulted.

The exhibition was called I like America and America likes me and it had a powerful influence on the American artworld of the seventies, particularly performance art. The idea was that Beuys would not set foot on American soil and so when he arrived at the airport (in May 1974) he was met by an ambulance, wrapped in felt, laid on a stretcher, driven into NYC and carried up to the gallery.

Inside the Renne Block gallery prison-style bars had been built around one of the rooms, creating a sort of cage. Inside that room was some straw and a coyote. Beuys moved in with the coyote and lived with it for three days, wrapping himself in felt and getting a daily delivery of newspapers for the animal to defecate on and chew up. Visitors would come and look at them.

Two powerful slogans emerged from this exhibition: I am the Coyote and The Most Reviled Creature in America. The idea was that Beuys had found common cause with the coyote as being the “most reviled” creatures in America.

Here you can see a photo of Beuys wrapped in felt and the coyote looking on:

Photo by Caroline Tisdall

This is where my limited knowledge of all this runs out; I wish I knew more the fascinating ideas behind this exhibition but, as with the Special Unit artworks, there’s very little online about it and the people who know are either dead (Beuys died in 1986) or unobtainable (Jimmy Boyle lives between France, Morocco and Thailand and doesn’t answer emails).

But I searched the terms “coyote symbolism” and came across some extraordinary material. According to the Spirit Animal website: “The coyote totem is strikingly paradoxical and is hard to categorize. It’s a teacher of hidden wisdom with a sense of humor, so the messages of the coyote spirit animal may paradoxically appear in the form of a joke or trickery. Don’t be tricked by the foolish appearances. The spirit of the coyote may remind you to not take things too seriously and bring more balance between wisdom and playfulness.”

Did Beuys know about the symbolism of the coyote? It goes a long way to explain his approach which, on the one hand is very down to earth and simple, open to all; but on the other hand he was a very divisive figure who was rejected by much of the art establishment of Germany. Even to this day he is divisive; in 2019 Richard Demarco put on a retrospective of his work at the Edinburgh Festival and to this day people ask: “is this art?”

Jimmy Boyle opens the floodgates

Meanwhile, back in Scotland, a dam had burst – that is how Jimmy Boyle describes his outpouring of creativity when he got into sculpture and writing. In Barlinne Prison’s Special Unit he was able to divert his tremendous energy from fighting the system to creating artworks. But it almost never happened.

One of the best-known stories from the Special Unit was when Boyle arrived the head warder, an enlightened prison officer called Ken Murray, gave him a pair of scissors to open a parcel. To give “Scotland’s most dangerous criminal” a pair of scissors – a potentially lethal weapon – was an act of faith that showed Jimmy Boyle he was being trusted for the first time in years. It worked, and Boyle became one of the leading lights in the therapeutic community where prisoners and staff would together organise their schedule, menu and visiting hours.

Boyle rapidly integrated into the small community of ten prisoners, all of whom had been classified as “most dangerous” but he was nowhere near ready to do art. He later recalled that he saw art as almost something alien, a million miles from the macho culture he’d grown up in.

Scotland’s first art therapist – Joyce Laing – started visiting the unit and tried to get the inmates interested in practicing art. But it wasn’t working: the prisoners would sit round watching but they weren’t engaging. Joyce had decided to give it one last try and then she was going to give up, but before leaving she left a lump of clay and said, “maybe one of you can do something with this.”

When she came back for her last art class, Joyce was delighted to find that Boyle had created a sculpture out of the clay – a stick figure sitting down, surrounded by spear-like bars of a cage. I’m not sure exactly what happened next but the artworks came pouring out; not only sculptures, but also an avalanche of writing – not just the book that made him famous (A Sense of Freedom), but a series of stream-of-consciousness writings on all sorts of materials (paper was in short supply) written in a handwriting that was so small it’s barely possible to read. I’ve seen some of this material in one of the private archives and I’m pretty sure none of it has been published.

Enter Richard Demarco

Meanwhile, over in Edinburgh, Richard Demarco had been organising his own creative flood: he was to the Scottish arts establishment what Beuys was to the Germans – an annoying impresario who didn’t play by the rules, didn’t respect the arts establishment and kept coming up with new ideas, introducing new artists from all over the world and generally shaking things up. If you look at this link, Demarco’s CV-cum-biography, you’ll see the incredible amount of action he created on the Scottish arts scene over the last 50 years. 1974 was a particularly productive year.

Demarco picked up on the creative energy that was coming out of the Special Unit – the first time a prison had allowed such an outpouring of artistic expression – and was allowed to visit the unit with groups of artists. I presume this was also unprecedented and was, no doubt, one of the factors that the Scottish prison authorities disapproved of and used as an argument to shut it down in 1994.

In August 1974 Richard Demarco organised an exhibition in Edinburgh that was part of his sprawling Edinburgh Arts events. The exhibition included some sculptures by Jimmy Boyle who was still, at the time, very much in prison for murder.

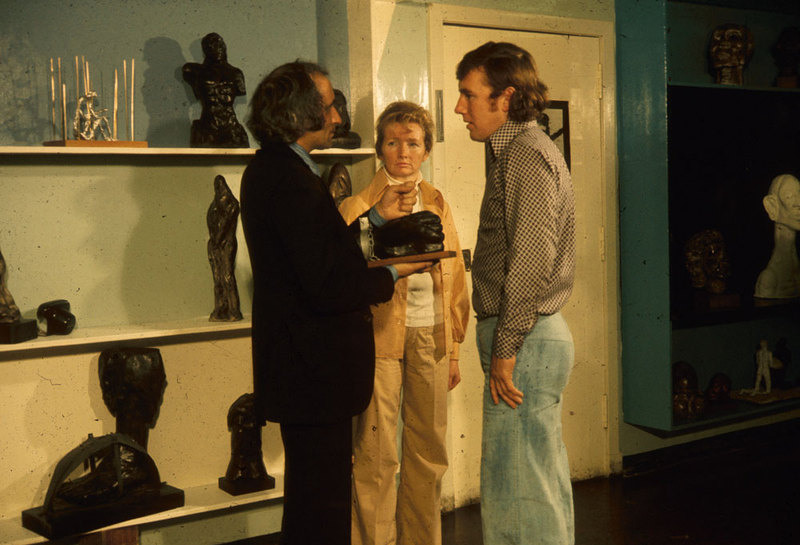

Here you can see a photo of Boyle, Demarco and the art therapist Joyce Laing (note the bronze copy of Boyle’s first sculpture on the upper left):

Thanks to the Richard Demarco Gallery for the photo.

The fact that Jimmy Boyle was allowed out of prison to attend this event was, presumably, unprecedented in Scottish prison history – and the forces of reaction at the prison service and Scottish government must have been furious.

The other extraordinary thing that happened at that exhibition was that Jimmy Boyle met Joseph Beuys, who had recently come over from New York after his coyote exhibition.

Boyle had presumably been told about the coyote exhibition by a mutual friend – Caroline Tisdall, an art critic for the Guardian and the photographer at the coyote exhibition. She was also a regular visitor to Boyle in the unit, and one of his most powerful advocates.

The story I heard from one of the artists who had been there was that Boyle went up to Beuys and said “I am the coyote!” I’m sure that those words, and their respective approaches to art, created a powerful bond that broke through all the conventional hierarchies of the art world.

Joseph Beuys went on to do some important work in Scotland. He also visited the Special Unit and represented Jimmy Boyle at a press conference that presented Boyle’s exhibition In Defence of the Innocent, at the Richard Demarco Gallery in 1976.

The most extraordinary thing that Beuys did for Boyle was go on hunger strike in 1980 – in protest at the prison services inexplicable transfer of Jimmy Boyle from the Special Unit to a “normal” prison at Saughton, Edinburgh.

The Scottish Prison Service, still feeling the humiliation that the Special Unit had brought down on them by showing signs of free expression, that they were determined to crack down. They didn’t yet have the political courage to close the unit down – that would happen about 14 years later – but by removing Jimmy Boyle and the enlightened head warder, Ken Murray, they were able to emasculate it. Their public intention was to “test” Boyle and make him “prove” that he could behave properly in a jail with the usual harsh military routines. Boyle survived this episode, but he was no longer allowed to practice his art and have free access to visitors. It must have been devastating and was, I’m sure, one of the factors that resulted in Boyle leaving Scotland soon after he was set free.

Two things bring all these historical events up to date: firstly, almost nothing has happened in terms of prison reform in UK, apart from a PR makeover, and surely the Special Unit deserves looking at in a serious way as they have a lot to learn from the experience (I think they should set up a permanent exhibition and archive in Glasgow).

Secondly, in 2019 there was an exhibition at the University of Hull with some of the artworks that were produced around the Special Unit in that incredible year (1974). I had posted a link to the exhibition but it’s been taken down.

I wrote this article as a supplement to a short piece I published in The Sunday National newspaper, a Scottish newspaper, which is worth looking at as it asks the question, why do we imprison people?

#

Postscript: This article was written from all sorts of fragments I picked up over the last 50 years – starting with my own visit to the Special Unit with my Mother, who published Jimmy Boyle’s books, conversations with Bill Beech who was behind the recent exhibition in Hull and also the scriptwriter for a great film that came out of that period: Silent Scream (1990).

I’d also like to thank Richard Demarco for making these photos available.

I took the above photo outside the exhibition in Hull. It was taken in 1974 and on the left you can see Richard Demarco, the impresario who introduced this prison experiment to the art world. On the right is the great Joseph Beuys.

Finally, here are some really interesting videos

This is an old documentary (1980s) about Jimmy visiting his home turf in Glasgow and asking if opportunities for young people have improved: Jimmy Boyle larchgrove & castlemilk – YouTube

And here’s a conversation between Jimmy and Ricky Demarco, shot in 2018: 1) Demarco and Boyle in coversation Dec 19 version – YouTube

- Introduction to 12 Jobs in 12 Months - April 23, 2024

- Why am I writing a Book About 12 Jobs in 12 Months? - April 4, 2024

- A Guide to Ukraine’s Future - February 19, 2024

Jimmy Boyle has been a fantastic ambassador for Scottish art and Scotland.

There are not enough words to describe the different phases of life that he has had to endure.

There should be a curriculum in all Scottish schools to educate the population and celebrate the amazing human being he turned out to be, whether it was down to the Scottish penal system or the individual is irrelevant.

In Jimmy we have someone to be proud of and we should tell the world.

Hi Rupert,

I’m currently working on a PhD which includes aspects of Demarco, Jimmy Boyle, The Special Unit and Beuys. I also took part in a panel discussion in Hull with Demarco and others. Best wishes, Giles.

Hi Giles, I think we may have met many years ago. I would love to see your Phd paper. Will you publish it or share it?

P.S…I think Jimmy was unique. Not the typical hard man in Scotland. There was a a bit of that within him but it certainly wasn’t a prominent part his personality or being.

Met others in the unit and they had different vibes. One them ended up living with an artist near walkerburn. Totally different.

I am the mural artist who wirked with Jimmy and the others at the Special zUnit in 1976 doing the mural depicted in the article. I stay in touch with Jimmy and have archives on the Unit.

He actually wrote Joseph Beuys that he was the coyote, which made Joseph come to visit him, from what I remember.

Are there images of the mural in the exhibit?

Also, it is archived at The Peoples Palace Museum in Glasgow, and there is a book on The Art of the Special Unit

In reply to Beth Shadur: Thanks for your comment. I’m not sure if there are photos of the mural at the exhibition as there are so many photos there (hundreds). I’m also not sure about any book on the issue but would be most grateful if you could send me a title or link. All the best, Rupert

Rupert, this is a fantastic article and you drive the audience to think again and again about the same question: punishment or education?

Either option will cost the same money to any country. Is it time to revisit the question?

Those people in jail sometime have such energy (often too much) and this force needs to be channelled in a creative or at least a positive way.

For the last 7 years I’ve been working on a documentary film starting in a Romanian prison (about a great artist who revealed his talent inside prison). I’m interested in documenting these experiences in other countries too.

I heard that you helped this exhibition about the Special Unit. I wish to visit it before its end in January ’20.

Wish I had known you were working on this when we met ….

I was working with Richard Demarco helping to coordinate jimmy’s

exhibition and was invariably needing to go to Barlinne’s special unit a few times.

Jimmy cooked me supper as I was going to be in Glasgow later on. He advised me that the safest place to have diner was there because I did not know my way around Glasgow, being a Peebles gal. Quite funny that…

Here’s another instance I would like to reflect on: Turkish Constitutional Law; there are some articles that cannot be changed. There is this huge controversy going on about Article 301 which you can see here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Article_301_(Turkish_Penal_Code)

Basically, freedom of expression is banned in Turkey. Especially over the last 20 years when we’ve been under the reign of the AK Party, led by President Erdogan. This article against freedom of expression about the government, or President Erdogan himself, in a negative manner has caused many writers, artists or other political party members to be imprisoned.

I have a close friend who’s been imprisoned several times because he supports TIP (Turkish Socialist Party) and protested against the current regime. He told me about the prison system. They’re imprisoned as “opinion criminals” and are put in a different type of unit. What they do is wake them up at 8 a.m. and take registration, serve breakfast and then it’s time for them to go out at the ‘garden’ to walk, talk, smoke a few cigarettes and so on. They basically do nothing all day long; just hang around. All prisons have a small library. The books they can read are restricted and they cannot read certain thought-provoking or anti-government books or magazines. This is applied to each and every type of prisoner in Turkish prisons.

For instance, recently, from the start of the Covid-19 epidemic, many ordinary prisoners that had a short time left to serve were let go and the violence rate has doubled regarding violence against women, drug trafficking, rape and murder. President Erdogan has been imprisoning every artist (even comic book illustrators), anybody that is not in favour of his regime and writes/talks/protests regarding himself or his government. He does this by using Article 301.

In terms of any classes or courses or any collaborations with artists or NGOs, there are not many examples although there’s also another article in the law. It depends on who runs the prison – whether someone in favour of the government or in favour of reform. In the previous years, I remember one theater workshop in one prison put a play on stage. I wish some prison reform was made in Turkey but given the circumstances right now, we’re still waiting for the Presidential Elections of 2023.

This article has popped up many questions about the prison system in several different countries.

It reminded me of a talk I had with a former Dutch prisoner. He told me that their prisons are in some ways better than the ‘outside’. He said they even had TVs in their cells and that the system running ‘inside’ was liberal and comfortable. Prisoners could choose from a wide selection of classes and courses.

I believe that if given a chance, even the most dangerous prisoners could develop themselves and make progress on various topics and classes including different genres and mediums of art. Making art helps each and every human being express themselves. And that would definitely liberate them.

The issue you’ve presented in this article will, I hope, motivate everybody including governments to think more about how they run these institutions; not just prisons but also mental hospitals.

Firstly, the death penalty must be banned. Secondly, collaborations must be made with other institutions and NGOs to advance these institutions. Reforms must be made. your article deserves to trigger a snowball effect.